Changelog

Dec 7th, 2024: I updated a few sections of this guide to reflect the changes in the most recent releases. Nothing much has changed other than the default cryptogaphic library, which is now mdebtls. The -ct mesh issues are still there with the ath10k based radios but my instructions to simply install the non-ct ones work as before. A couple other things: (a) just tested with 24.10-rc2 (an upcoming release candidate) and everything seems to be working as expected; (b) the old TP-Link TL-WDR4300 is still able to run the upcoming release (kudos to the OS devs!) and the C7 continues to be one of my favorite cheapo mesh routers; (c) added a note to onemarcfifty’s video tutorial to let people know that the luci-proto-batman-adv has not been updated in a long time and does not seem to be working anymore but this only affect the people trying to set it up via the web interface, not via ssh (we’re good!).

Aug 12th, 2023: The upcoming OpenWrt version 23.05 will bring a few changes to the way we configure VLANs. I’ll update the guide once 23 becomes the current stable. Until then, if you are using version 23 and playing aorund with VLANs, then refer to the DSA mini tutorial and converting to DSA user guide.

Dec 21st, 2022: Minor updates to streamline a few commands and to add a note here that this guide is still valid for the current stable release version of OpenWrt (22.03.2). I should also mentioned that a user (Iglói) reported that the Linksys EA8300 might not be the best choice for a high-end mesh node because VLAN support is limited in the IPQ40xx hardware. However, I’ve never tested that myself and after glancing over the forum posts, it seems the issue has been fixed in the latest release. In any case, if you want to consider other high-end alternatives, check out the Linksys WRT23x and the ZyXEL NBG6817.

May 4th, 2022: Marc (OneMarcFifty) has published a video tutorial describing how to configure OpenWrt and batman-adv via LuCI, which is only possible because he also wrote a package that gives luci support for the batman-adv protocol (luci-proto-batman-adv). I added a reference to Marc’s tutorial at the end of the Other similar mesh solutions section.

February 4th, 2022: Updated the Hardware-specific configurations section to include info about an issue affecting the GL-AR750 and the AVM Fritz!WLAN Repeater 1750E. Also, the ath10k troubleshooting instructions were slightly modified to make them more general. Thanks to JF and Erik for testing and letting me know about the affected devices and solutions.

January 1st, 2022: Added a new section called Advanced features to cover batman-adv features not previously described in the basic implementation section. The first included feature was the use of multi-links to improve performance and reliability. The subsection includes examples and a how-to for the implementation of multi-links. In addition, I changed the Linksys reference in Hardware to the more stable Linksys EA8300 as reference of a high-end device. I’ve not personally used it but have read reports of good experience with it by the OpenWrt forum user 16F48, for example.

October 6th, 2021: The guide was completely updated to make it consistent with the current stable release, namely OpenWrt 21.02. In brief, most of the changes had to do with the new network syntax and increased hardware requirements. More specifically, OpenWrt 21.02 drops the use of ifname and make a more clear distinction between layer 2 and layer 3 configurations in the /etc/config/network file. In addition, the minimum requirements to run OpenWrt are now 8MB of flash memory and 64MB of RAM. The latter change prompted me to use a new TP-Link router for the examples, namely the TL-WDR4300, instead of the old WR1043ND (v1). This new router is still a low-end device, which makes very affordable and easy to find worldwide, but contrary to the WR1043ND, it is actually a dual-band router. This was an opportunity to illustrate wireless segmentation for mesh vs. non-mesh communication, which is something I think is almost required in most use cases, so the new guide makes use of it by default. I also took this opportunity to update many, many other things. To mention two main ones: (a) at the end of the OpenWrt installation and initial configuration section, there’s now a description of how to build custom images that contain all the required mesh packages; and (b) the section Bonus content: Moving from OpenWrt 19 to 21 was update to help users who followed the earlier version of this guide to transition to the new release. This was a big one and took a few days to get it done. Hope you find it useful!

September 16th, 2021: Updated the information about OpenWrt 21 in the section Bonus content: Moving from OpenWrt 19 to 21. In brief, DSA support is still very limited and OpenWrt has officially started rolling out version 21 with the release of OpenWrt 21.02. I’m currently testing the new version and network configuration on a few devices and once I get everything running as well as it was in version 19, I will update the entire article to reflect the new (and current) configuration. It is, of course, still possible to download and use the latest OpenWrt 19 images, which should be just fine for a long time still. However, if you want to make use of OpenWrt 21, then read the aforementioned bonus section for guidance on the syntax changes and updated hardware requirements.

July 6th, 2021: Added information about transitioning from OpenWrt 19 (current stable release) to OpenWrt 21 (next stable release) to a new section called Bonus content: Moving from OpenWrt 19 to 21. In brief, the next stable release includes changes to the network configuration syntax that are incompatible with this guide. Once the release version 21 becomes the current stable, however, I will update the main guide to reflect those changes. In the meantime, I added a few references to the OpenWrt forum that should help anyone interested in using version 21 instead of 19. Thanks to Steve for testing and sharing his batman-adv configuration running on OpenWrt 21.

Feb 17th, 2021: Per a reader’s suggestion (Joshua), I added a vi cheat table that has a summary of the main commands, and in the Mesh node basic config section, I included additional instructions on how to copy and paste the configuration files from one mesh node to another using scp. (Alternatively, it’s also possible to do so using Luci’s backup/restore option.)

Jan 9th, 2021, Update #2: Added instructions on how to automatically upgrade all installed packages with a single command. This information is in Updating and installing packages.

Jan 9th, 2021, Update #1: Added a new section about hardware-specific configurations that are sometimes required for enabling the mesh point mode of operation.

Dec 7th, 2020: Publication of the original guide

Introduction

In this tutorial, we will learn how to create mesh networks (IEEE 802.11s) using OpenWrt and the layer-2 implementation of the Better Approach to Mobile Adhoc Networking, called batman-adv. All the software mentioned here is free and open-source, as opposed to commercial alternatives (UniFi Mesh or Google’s Nest Wifi).

This is not meant to be an exhaustive presentation of any of the covered topics. If you have suggestions on how to improve this guide, feel free to get in touch with me. I’m always eager to learn new things and share them. Also, I plan on updating this article every once in a while to best reflect my knowledge about the topics covered here and to add information provided by the readers. Check the changelog for updates.

Why am I writing this guide?

Even though the concept of mesh networking has been around for quite some time now, the documentation of its implementation is still scarce/nichey, proprietary, or outdated. I don’t feel qualified to speculate on why this is so but I find it odd because many of the radio devices found in popular wireless routers actually support mesh networking–but the original firmware rarely supports it.

My intention with this tutorial is to help closing the gap between concept and implementation of mesh networking using up-to-date software that anyone can download and install on cheap, commonly available hardware–primarily consumer wireless routers (from old to new, single- or multi-band) but the principles should be extendable to any cellphones, laptops, PCs or servers running Linux. The content is partially based on my own experience and builds upon the work of other, much more talented individuals who shared their knowledge on the Web. More specifically, the content is notably influenced by the following:

- Brian Innes workshop about using Raspberry Pis to create a mesh network for sharing sensor data wirelessly (Github repo)

- Andreas Spiess LoRa mesh project

- Maintaners of the OpenWRT documentation and the B.A.T.M.A.N. wiki

- Multiple users from the OpenWrt forum who shared their opinions over the years. To name a few, the users jeff, mcarni, oavaldezi, slh, and many others. Thanks for keeping the posts public.

Objectives

- Get familiar with

/etc/config/files in OpenWrt devices (namely,wireless,network,dhcp,firewall) to quickly and permanently configure mesh nodes. - Edit files directly from the terminal using the default text editor

vi. - Configure OpenWrt devices to play one of three possible roles in the network: (a) mesh node, (b) mesh + bridge node, or (c) mesh + gateway node.

- Install and configure the Kernel module

batman-advon an OpenWrt device using theopkgpackage manager. - Use

batctlto test, debug, and monitor connectivity within the mesh. - Use two radios to segment mesh (5Ghz) from non-mesh (2.4Ghz) wireless communication.

- Add encryption to the mesh network with the package

wpad-mesh-mbedtls. - Use VLANs to create

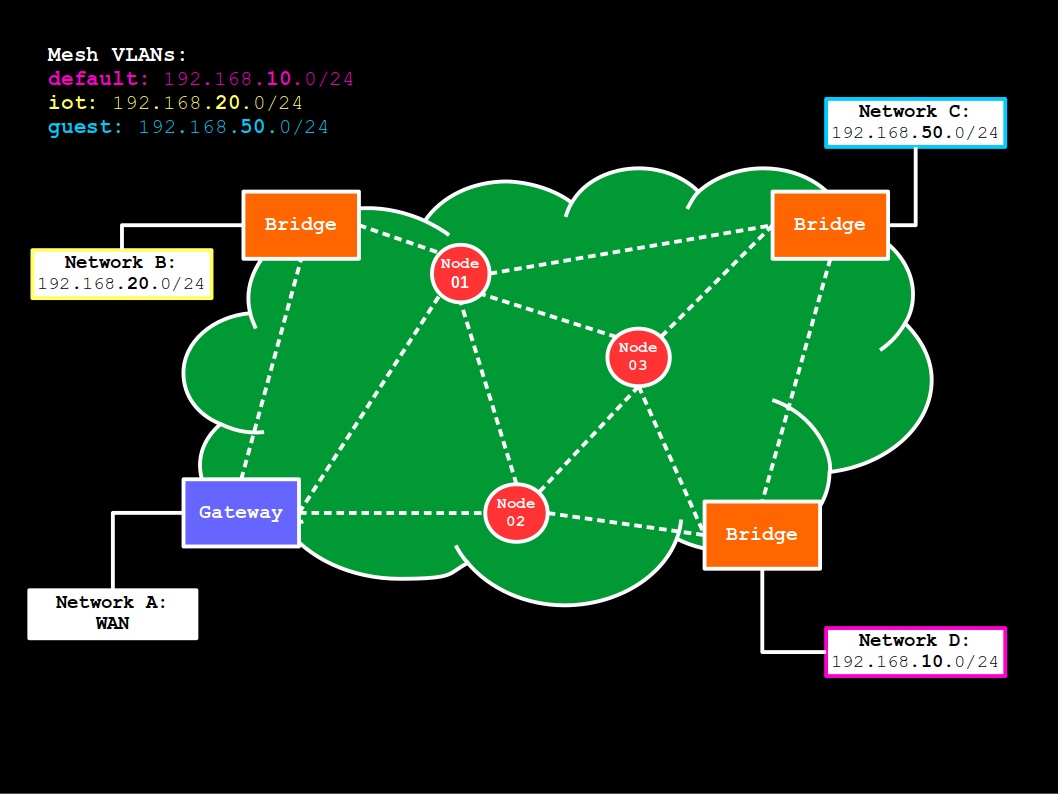

default,iot, andguestnetworks within the mesh usingbatman-adv.

Outline

From this point forward, the article is divided into four main parts:

- Concepts and documentation: Optional for advanced users. Brief introduction to just enough network concepts to allow the implementation of simple mesh networks. When appropriate, a link to the relevant OpenWrt documentation was also provided.

- Hardware: Optional for everyone. A few notes about the hardware used in the examples and recommendations for those who are planning on buying new/used devices for their mesh project.

- Software: Optional for everyone. A few notes about the software used in the examples.

- Implementation: Required. Step-by-step procedure to configure mesh nodes, bridges, and gateways. It goes from flashing OpenWrt to configuring VLANs with

batman-adv. You probably came here for this part.

Concepts and documentation

Main network definitions

- Mesh node: Any network device that is connected to the mesh network and that helps routing data to (and from) mesh clients. Here, however, if a mesh node acts as a bridge or gateway, it will always be referred by the latter role, even though by definition, mesh bridges and mesh gateways are also mesh nodes.

In addition, even though it’s possible to route mesh traffic via cable, in this tutorial, all mesh nodes are also wireless devices, meaning that they have access to a radio with mesh point (802.11s) capabilities. -

Bridge: A network device that joins any two or more network interfaces (e.g., LAN Ethernet and wireless) into a single network. Here, when a device is referred to as a bridge, it means that in addition to being a mesh node, the only other thing it does is bridge interfaces. But of course, a gateway device, such as a router with a built-in modem, or a firewall appliance, may also work as a bridge for multiple interfaces. The distinction in the examples is just used to highlight its main role in the network. Therefore, a mesh bridge in this tutorial is a mesh node that simply bridges the mesh network with a WiFi access point for non-mesh clients, for example, or its LAN ports.

- Gateway: A network device that translates traffic from one network (LAN) to another (WAN) and here, acts as both a firewall and DHCP server. (If there’s more than one DHCP server in the same network, they assign IPs to different ranges, such as

.1-100,.101-200, and so on.) -

DNS: In brief, a system for translating domain names (e.g.,

cgomesu.com) into IP addresses (185.199.108.153,185.199.109.153,185.199.110.153,185.199.111.153). DNS filtering systems, such as PiHole, work by catching such requests–usually sent through port53–and checking if the domain is blacklisted or not. In this tutorial, we will always use an external DNS server, such as1.1.1.1(Cloudflare) or8.8.8.8(Google), but if you have your own DNS resolver, feel free to use it instead when configuring your mesh network but then make sure the mesh network/VLAN has access to its address. - DHCP: An IP management system that dynamically assigns layer-3 addresses for devices connected to a network. For instance, it might dynamically assign IPs between

192.168.1.0and192.168.1.255(i.e.,192.168.1.0/24) to any devices connected to LAN. Of note, because this is a network layer protocol, it uses IP addresses, whereasbatman-advuses MAC addresses because it works at the data link layer (and therefore,batman-advactually doesn’t need DHCP and IPs to discover and manage mesh clients but we’re going to use them to make it more intuitive and easier to integrate mesh with non-mesh clients). - Firewall: A network system that monitors and controls network traffic, such as specifying rules for incoming WAN traffic (e.g.,

deny all), outgoing LAN traffic (accept all), geoblocking and IP filtering systems, intrusion prevention/detection systems (Suricata), and so on. OpenSense and pfSense are examples of dedicated firewall software. If a mesh node is acting as a mesh gateway, it’s imperative to configure the firewall or your mesh network will likely end up without access to external networks (e.g., WAN) and their services (e.g., DNS servers). - VLAN: A virtual LAN that is partitioned and isolated in a network at the layer-2 level. They are often followed by an integer to differentiate each other (e.g., VLAN 1, VLAN 50) and used to better manage network clients that belong to different groups (e.g., administrators, IoT devices, security cameras, guests).

Network topologies

Mesh networks

What are mesh networks?

Where can I learn more about mesh networking?

- Wikipedia articles about mesh networking and wireless mesh networks

- Peer-reviewed papers or books

Routing protocols

There are dozens of algorithms for routing packets in a mesh network. A few notable ones are the Optimized Link State Routing (OLSR) and the Hybrid Wireless Mesh Protocol (HWMP).

In this tutorial, however, we will cover only one of them, called Better Approach to Mobile Adhoc Networking (B.A.T.M.A.N.), because it has long been incorporated into the Linux Kernel and is thus easily enabled on Linux devices. It is also a fairly well-documented algorithm that has been continuously improved over the years. Another noteworthy feature of batman-adv is its lack of reliance on layer-3 protocols for managing mesh clients because it works at the layer-2 and its ability to create VLANs. Think of it as if it were a big, smart, virtual switch, in which its VLANs are port-based segmentations. If you want an interface to use a particular mesh VLAN, just “plug it” into the approriate port of the batX switch (e.g., bridge guest and bat0.2 to give the guest network access to the bat0 VLAN ID #2).

batman-adv

As mentioned before, B.A.T.M.A.N. has gone through multiple changes over the years, which means that there are actually multiple versions of the algorithm. I’ve had a good experience with B.A.T.M.A.N. IV and therefore, the examples here make use of it. However, you are free to try whatever version you want and even run them in parallel to each other, by assigning a different batX interface to each version of the algorithm (versions are chosen with option routing_algo in the /etc/config/network config file for each enabled batX interface).

Config-wise, there’s very little to do because the default settings should work very well in most environments. One exception is when you have multiple gateways in the network to provide high availability, for example, and you might want to let each mesh node know about them and their speeds to better route the mesh traffic. This requires setting option gw_mode to server or client, for example. Many other tweaks that are not covered here are described in their wiki.

batctl

Another very cool feature of B.A.T.M.A.N. is the ability to test, debug, monitor, and set settings with the package batctl. A few noteworthy options:

- Ping mesh node/client with its MAC address

f0:f0:00:00:00:00batctl p f0:f0:00:00:00:00 tcpdumpfor all mesh traffic in thebat0interfacebatctl td bat0- Prints useful stats for all mesh traffic, such as sent and received bytes

batctl s - Shows the neighboring mesh nodes

batctl n - Displays the gateway servers (

option gw_mode 'server') in the mesh networkbatctl gwl

It goes without saying that if you want to dive deep into batman-adv, you should take a good look at batctl, too.

Hardware

Unless otherwise specified, all mesh nodes used in the various implementations had the following hardware:

- Device: TP-Link TL-WDR4300 v1.0 - v1.7

- SoC: Atheros AR9344

- WLAN Hardware: Dual-band (Atheros AR9344, Atheros AR9580)

- CPU:

560 Mhz - Flash memory:

8 MB - RAM:

128 MB

This is a low-end, Atheros-based dual-band router that satisfies the minimum hardware requirements imposed by OpenWrt 21–namely, at least 8MB of flash memory and 64MB of RAM. However, the general ideas presented here should apply to any wireless device that meets the following criteria:

- Compatible with the latest OpenWRT version. Refer to their Hardware List;

-

Has access to a radio that supports the mesh point (802.11s) mode of operation. If you already have OpenWrt installed on a wireless device, you can type

iw listand search formesh pointunder Supported interface modes, or simply check if the following command outputs* mesh pointbelow the name of a detected radio (e.g.,phy0,phy1):iw list | grep -ix "^wiphy.*\|^.*mesh point$"If it does, then the associated radio can be configured as a mesh point.

Now, if you’re looking for devices to buy and experiment on, my suggestion is to look for high-end dual-band wireless routers to allow a better segmentation of the wireless networks. If you can afford spending more for a mesh node, look for tri-band devices. Netgear and Linksys have solid options that are compatible with OpenWrt. For example, the Linksys EA8300 tri-band wireless router would make for a good high-end mesh node:

For single-board computer (SBC) fans like me, you can run OpenWrt with most of them and then use a combination of on-board wireless and USB adapter to create a powerful mesh node. ClearFog boards with one or two mini PCIe wireless cards would make very good candidates for such a project, for example:

Of course, you can install OpenWrt on bare metal x86-64 machines (e.g., standard PC or server running Intel/AMD), which will give you lots of options to put together an impressive mesh device. However, if you just want your work/home laptops/PCs to be part of the mesh (i.e., become a mesh node), there are better alternatives than installing OpenWrt as its OS. For example, you can run OpenWrt with a virtual machine or as a docker container. Naturally, it’s also possible to configure batman-adv on Linux distributions other than OpenWrt, such as Arch, Debian, and Ubuntu. See Getting started with batman-adv on any Linux device.

As mentioned before, even if the existing/on-board radio of your SBC/laptop/PC/server does not support the mesh point mode of operation, you can always buy a compatible PCIe card or USB adapter to turn your device into a mesh node and then use the other radio for another purpose. For example, many Alfa Network adapters can operate in mesh point mode, like the cheap AWUS036NH:

All that said, most home users will be just fine with a cheapo, used, old, and single-band router. For a brand reference, TP-Link has good and affordable devices that can be used in a mesh networking project without issues. If you’re new to this, start from here (small, simple) and think about efficiency over power. You don’t need to drive a Lamborghini to get a snack at the grocery store. For additional resources, skip to the section called Useful hardware resources down below.

Hardware-specific configurations

Every once in a while, users run into hardware that is capable of operating in mesh point mode but the default OpenWrt firmware uses a module for the wireless adapter that is loaded with incompatible parameters. Here is a list of a few of the known ones and their solution.

ath9k modules

If your device uses the ath9k module, there’s a chance that you’ll need to enable the nohwcrypt parameter of the module to use the mesh with encryption. First, however, try without changing the default module parameters. After rulling out possible typos in the network and wireless configuration files, try the following:

- Edit the

/etc/modules.d/ath9kfile and addnohwcrypt=1to it. If there’s something in the file, use a whitespace to separate parameters. - Save the file, and reboot your device.

- Once the device comes back, check if

nohwcryptis now enabled by typingcat /sys/module/ath9k/parameters/nohwcryptIf

nohwcryptis enabled, the output will be1; otherwise, it will be0. - Check your mesh configuration once again and add encryption to your wireless mesh stanza.

-

Known affected devices:

brand model version OpenWrt release TP-Link WR-1043-ND 1.8 19.07

ath10k modules

I’ve noticed that radio devices that use the ath10k module and more specifically, the ones using ath10k-firmware-qca988x-ct, are not able to operate in mesh point mode by default. If you check the syslog (logread), you’ll notice that there will be a few messages stating that the ath10k module must be loaded with rawmode=1 to allow mesh. However, I’ve tried that before without much success. Instead, my current recommendation to get mesh point working with any of the QCA988x hardware is the following (Internet connection required to download packages via opkg):

- Check which

athmodule is installed viaopkg:opkg list-installed | grep -i athwhich should show at least one

ath*-firmware-qca988*and anotherkmod-ath*packages installed. - Try official alternatives to them:

- For the

ath*-firmware-qca988*alternatives, check the OpenWrt Firmware index for similar ones and favor the ones that match your hardware (e.g,QCA9887) before trying the more generic ones (e.g.,QCA988x). - For the

kmod-ath*alternatives, check OpenWrt Kernel Modules index. - Of note, if the installed modules are Candela Tech (contain the suffix

*-ct), then (a) remove the -ct packages and (b) install compatible non-ct ones. For the TP-Link Archer C7, for instance, you can replace the -ct module as follows:opkg update opkg remove ath10k-firmware-qca988x-ct kmod-ath10k-ct opkg install ath10k-firmware-qca988x kmod-ath10k

- For the

- Reboot your device and then check the status of your mesh network afterwards. If that does not work, check

logreadagain and if possible, try another module until you find a good one.

-

Known affected devices:

brand model version OpenWrt release AVM FRITZ!WLAN Repeater 1750E - 21.02 GL.iNet GL-AR750 - 21.02 TP-Link Archer C7 2.0, 4.0, 5.0 19.07, 21.02, 22.03, 24.10 TP-Link Archer C7 US 2.0 19.07, 21.02

Useful hardware resources

These are a few resources that I’ve used in the past that you might find useful when looking for mesh compatible devices:

- OpenWrt:

- Linux Wireless wiki:

- The wiki has a list of existing Linux wireless drivers that mention whether it supports

mesh pointor not. To search for specific devices, my recommendation is to (a) open the page of a driver that supports mesh (e.g., ath10k), then (b) look for supported devices under it, and finally, (c) go to OpenWrt’s Extended Table of Hardware and in WLAN Hardware, enter a supported device found on the Linux Wireless wiki (e.g.,QCA9880). This will create a filter to show only devices that contain the given hardware and should provide you a starting point for further research.

- The wiki has a list of existing Linux wireless drivers that mention whether it supports

Software

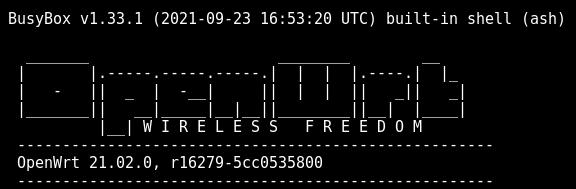

Unless otherwise specified, all mesh nodes were running the following software:

- Operating System:

- Firmware: OpenWrt

21.02.0or higher - Linux kernel:

5.4.143or higher

- Firmware: OpenWrt

- Packages mentioned in the tutorial:

batctl-full=>2021.1-1kmod-batman-adv=>5.4.143+2021.1-4wpad-mesh-mbedtls=>2024.09.15~5ace39b0-r1

To find out the version of all installed packages, type

opkg list-installed

or if you prefer to filter the output, use grep. For example, the following will show the version of all installed packages containing bat (e.g., batctl, kmod-batman-adv):

opkg list-installed | grep bat

Huge differences in firmware, kernel, or package versions might make the implementation of a mesh network a little bit different than the way it was explained here. Of note, devices running the batman-adv version 2019.0-2 and older are certainly incompatible with the instructions found in this tutorial, the reason being that the module was modified after then to better integrate with the network interface daemon. Fortunately, the implementation using old modules is just a simple as with the latest one. Check what the B.A.T.M.A.N. wiki has to say about it. However, it’s worth mentioning that with old batman modules, changes to /etc/config/network will likely require a reboot instead of simply reloading /etc/init.d/network.

Also, I’ve noticed that when installing kmod-batman-adv, the package manager will install a minimal version of batctl, called batctl-tiny, that lacks some of the options mentioned here (e.g., batctl n and batnctl o). However, if you install batctl first and then kmod-batman-adv, the package manager will preserve batctl-default, which has most of the batctl features. In this tutorial, however, we will use the batctl-full package that contains all features referred to in the batctl manual.

Finally, the installation of wpad-mesh-mbedtls will conflict with the already installed wpad-basic-mbedtls package (or any other wpad-basic* package, for that matter). This means you have to remove the latter before installing the former. To remove the wpad-basic-mbedtls or any other conflicting wpad-basic package, simply type

opkg remove wpad-basic*

VI text editor

The default text editor in a standard OpenWrt image is vi, which is an old, screen oriented editor that most modern users will find counterintuitive to use. Fortunately, once you get the hang of it, vi becomes very easy to use and it becomes a very convenient way of editing config files. Here’s all that you need to know about using vi in a terminal:

You can open a file by adding the filename as an argument to vi, as follows

vi /etc/config/network

and if the file does not exist, vi will create one with that name.

By default, vi will start in command mode. Such a mode let’s you navigate the file with the arrow keys and use the delete button to delete characters. (Also, in command mode, you can type dd to delete entire lines, which is very useful if you need to delete lots of things quickly.)

However, if you need to type characters and have more flexibility to edit the file, you need to tell vi to enter insert mode. To enter insert mode, type (no need to hit return/enter afterwards)

i

and at the bottom of the screen, you will see that it now shows a I to indicate that vi is in insert mode. You can now type freely and even paste multiple things at once in insert mode.

When you’re done, press the button Esc to go back into command mode. Notice that at the bottom of the screen, now there’s a - where the I was, which tells you you’re in command mode once again.

In command mode, you can then write changes to the file by typing (followed by return/enter)

:w

Now you’ve saved the file. To quit, type

:q

Alternatively, you can write and quit by simply typing :wq.

vi has other commands as well but honestly, that’s pretty much all that you need to know about vi in order to use in the examples covered here. Give it a try!

VI cheat table

| mode | key/command | action |

|---|---|---|

| command | i key |

Enter insert mode |

| insert | Esc key |

Return to command mode |

| command | dd (or hold d key) |

Erase entire row |

| command | :w + Enter/Return |

Write to file |

| command | :q + Enter/Return |

Quit to terminal |

| command | :q! + Enter/Return |

Quit without saving changes |

| command | :wq + Enter/Return |

Write to file and quit |

Alternatives to VI

Now, if you still don’t like to use vi, you can always transfer files from your laptop/PC to OpenWrt via sftp, for example, or utilities like scp.

Implementation

In this section, we will see how to configure four mesh nodes in three different network topologies. More specifically:

- Gateway-Bridge: A mesh network in which one node plays the role of a mesh gateway and another, of a bridge, while the remaining are just mesh nodes. This is a very typical scenario for a home or small office, for example.

- Bridge-Bridge: Two nodes play the role of a bridge, therefore making the mesh network transparent to the external (non-mesh) networks.

- Gateway-Gateway: Two nodes play the role of a gateway to provide high-availability to mesh clients/nodes.

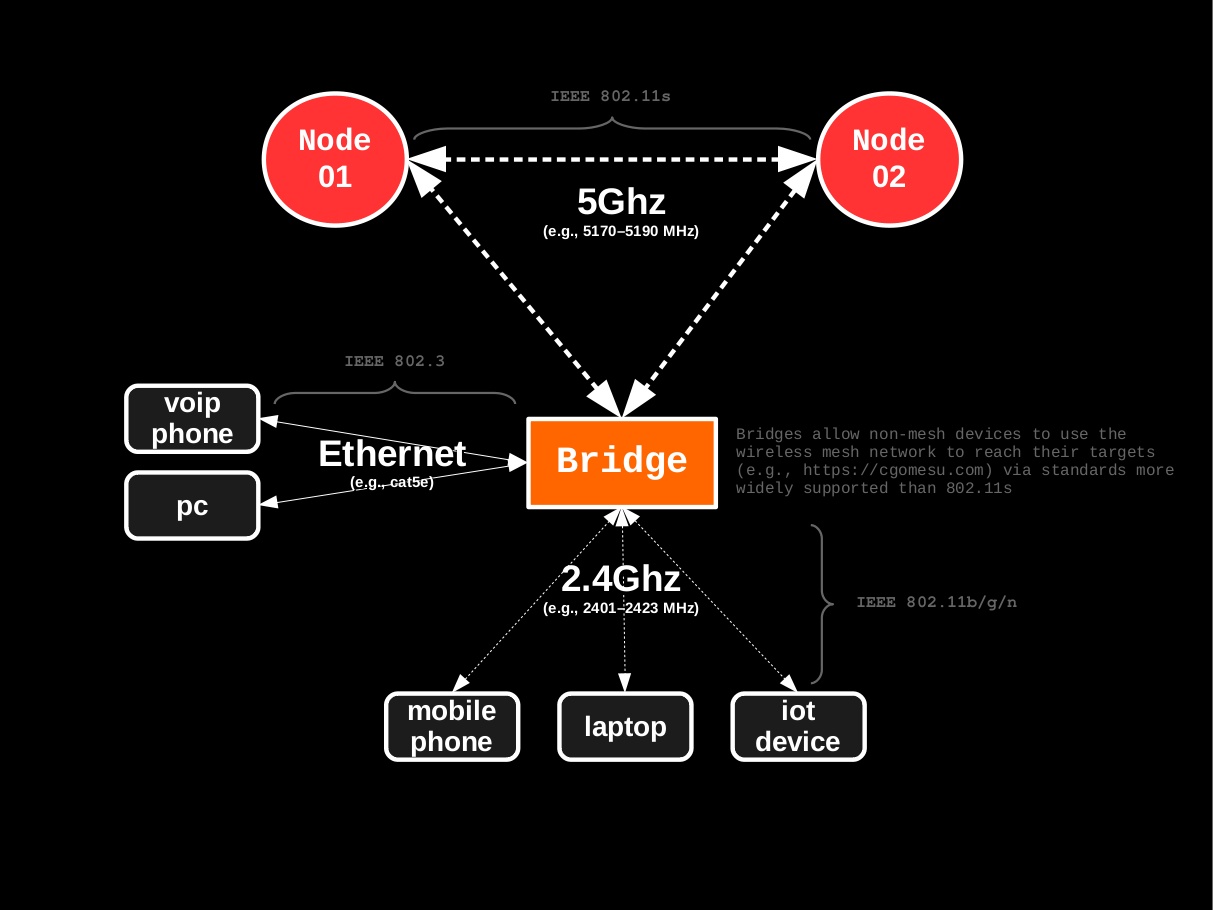

In all such cases, we will use the 5Ghz radio exclusively for mesh wireless traffic, while the more widely compatible 2.4Ghz radio, as well as Ethernet connections, will be left available for non-mesh wireless traffic:

Segmentation of mesh vs. non-mesh traffic is not a requirement but an option that greatly improves performance. If your mesh devices do not support dual-band, simply assign the same radio for both mesh and non-mesh wireless interfaces.

First, however, we will start with the aspects that are common to all topologies, such as planning the mesh network, and the installation and basic configuration of OpenWrt mesh nodes. Then, we will move to the specifics of each of the aforementioned mesh network topologies. Finally, we end the section with a slightly more complex scenario to illustrate how to create mesh VLANs with batman-adv and a very brief introduction to using batman-adv on other Linux distros.

Even though the examples show static nodes, none of the mesh nodes need to be static. The mesh network and its components can be partially or totally mobile. For example, if some of your nodes are mobile units (e.g., vehicles, drones, robots, cellphones, laptops), they can leave and join the mesh, recreate the mesh elsewhere, join a completely different mesh, and so on. The routing algorithm (batman-adv) will automatically (and seamlessly) take care of changes to the network topology. (But of course, if there’s a single gateway and it does not reach any node, the network is bound to stop working as intended without proper configuration to handle such scenarios.)

Planning

Just like any other type of network, deploying a mesh network–especially over large areas, with dozens of nodes–requires a fair deal of planning; Otherwise, you are bound to experience, for instance, bottlenecks, uneven access point signal quality, and unstable WAN connectivity across the mesh. Also, features like high availability go well beyond the configuration and topology of a mesh network (e.g., power source, whre your WAN connections are coming from, and the hardware you are using all play important roles when it comes to high availability). Mesh networks are very, very easy to scale but planning is key.

Eli the Computer Guy has an old video about mesh networks that goes into things like high availability and bottlenecks. If that matters to you, take a look. The relevant content starts at 03:30 and ends at 17:30, approximately.

The examples in this tutorial are simple by design–they were created to illustrate different scenarios in a way that makes it easy to understand what is going on. The idea is to use the examples as templates for more complex implementations.

OpenWrt installation and initial configuration

Now that you have the hardware, the first thing to do is to install OpenWrt. Flashing a default OpenWrt image onto a compatible device is a very easy and safe procedure because it’s been tested multiple times. (For extra safety precautions, you might want to search the web for your-device + openwrt to see if there’s any indexed forum post or comment regarding installation issues and bugs, for example.)

If you’re new to all this, the folks at OpenWrt were kind enough to provide a plethora of instructions on how to install and uninstall OpenWrt and even put together an installation checklist. At the very least, do the following:

- Look for your device’s model and version in the Table of Hardware and open its Device Page (e.g., TP-Link TL-WDR4300);

- Double check that the model and version match your device’s model and version in the Supported Versions table;

- In the Installation table, you will find a column called Firmware OpenWrt Install URL and another one called Firmware OpenWrt Upgrade URL. If your device is still running the original firmware, then download the binary from the Firmware OpenWrt Install URL column; otherwise, download the binary from the Firmware OpenWrt Upgrade URL column. Both files should have a

.binextension; - Regardless of the binary file downloaded, verify its checksum afterwards;

- Disconnect your laptop/PC from any access point or switch, and connect your laptop/PC directly to the device’s Ethernet port.

- Open your device’s web UI, go to its Settings and/or find the Firmware Upgrade option. Then, select the downloaded OpenWrt binary, and let it do its thing. Once it’s done, the device will reboot with OpenWrt installed.

- You should now be able to reach your new OpenWrt device at

192.168.1.1if connected to a LAN port. (Remember that all wireless interfaces are disabled by default, so you can only reach it via cable.)

If you followed these steps and successfully flashed the default OpenWrt firmware onto your device, then go ahead and skip to the Initial configuration section. The remaining part of this section is meant for advanced users who want to customize their image files.

If you’re an experienced user, you can use OpenWrt’s Image Builder to create a customized image that contains all the necessary packages and configuration files by default. This can save you a lot of time by letting you skip either partially or completely the remaining configuration instructions, depending on the level of specification of the make image build command.

To build a custom image file, first install the dependencies for your Linux distribution. Afterwards, follow these steps:

- Find the target for your device in the device’s OpenWrt page. For instance, for the TP-Link TL-WDR4300 v1, the target is ath79/generic;

- Navigate to the root of the available targets for the latest version of the OpenWrt 21.02 release (e.g.,

21.02.0); - Navigate to the root of your device’s target (e.g., for the TL-WDR4300, that would be ath79 > generic);

- Go to the Supplementary Files table at the bottom;

-

Download the image builder

.tar.xzfile (e.g., openwrt-imagebuilder-21.02.0-ath79-generic.Linux-x86_64.tar.xz) and check its hash afterwards:sha256sum openwrt-imagebuilder-*.tar.xz6354c0380a8cdb2c6a7f43449a7f6b3d04c4148478752a90f2af575ee182d2bb openwrt-imagebuilder-21.02.0-ath79-generic.Linux-x86_64.tar.xz -

If everything looks good, extract the image builder:

tar -xvf openwrt-imagebuilder-*.tar.xz -

Enter the image builder directory to start using

makeand then search for your device’sPROFILEname (e.g.,tplink_tl-wdr4300-v1), as follows:cd openwrt-imagebuilder-* make infotplink_tl-wdr4300-v1: TP-Link TL-WDR4300 v1 Packages: kmod-usb2 kmod-usb-ledtrig-usbport hasImageMetadata: 1 SupportedDevices: tplink,tl-wdr4300-v1 tl-wdr4300For long lists, you might want to filter the output via

grep. For example, to show only entries that containwdr4300, runmake info | grep -i wdr4300. -

Build customized images for your device’s profile. (See below for a table with a list of specific packages to add and to remove if you want to enable batman mesh support by default.) For example, to build images for the TL-WDR4300 (v1) without pppoe and IPv6 support and with a minimal LuCI and

batman-advmesh support, run the followingmake imagecommand:make image PROFILE=tplink_tl-wdr4300-v1 \ PACKAGES="uhttpd uhttpd-mod-ubus libiwinfo-lua luci-base luci-app-firewall luci-mod-admin-full luci-theme-bootstrap \ -ppp -ppp-mod-pppoe \ -ip6tables -odhcp6c -kmod-ipv6 -kmod-ip6tables -odhcpd-ipv6only \ -wpad-basic-mbedtls wpad-mesh-mbedtls \ batctl-full kmod-batman-adv" \ CONFIG_IPV6=nNotice that the prefix

-is meant to inform that the package should be removed from the default image of the chosenPROFILE. In addition, the inclusion ofCONFIG_IPV6=nis optional and only used here to completely disable the IPv6 configuration in the example. Other build configuration variables are also optional and can be modified by adding them to themake imagecommand. For more detailed information, runmake help.This will prompt your system to start downloading the required packages and then start building the firmware. Be patient because this operation can take several minutes.

-

Once the builder is done without any errors, navigate to the subdirectory

./bin/targets/<target>that contains the built image files, in which<target>is the device’s target. For the TL-WDR4300, for instance, the target isath79/generic, which means the built files are at./bin/targets/ath79/genericand you can navigate to it from the image builder root directory as follows:cd ./bin/targets/ath79/genericOf note, the

*.manifestfile contains a list of installed packages, which is useful if you need to double check which packages a given image contains by default. Theprofiles.jsonfile contains even more detailed information about the built image but it is in json format. If you havejqinstalled, however, you can parse it viacat profiles.json | jq .to get a more readable version. -

Personally, I like to copy all generated files to a location outside the image builder. To create a new location for the built images in your user’s Downloads directory, do as follows (suggested structure is

openwrt-custom-images/<release>/<device>):mkdir -p ~/Downloads/openwrt-custom-images/21.02/tl-wdr4300_v1Then copy all generated files to the new directory outside the image builder:

cp ./* ~/Downloads/openwrt-custom-images/21.02/tl-wdr4300_v1/Now you can safely go back to the root of the image builder directory and run

make cleanto delete all generated files. This is good practice if building multiple images with different features. - From this part forward, the procedure is the same as outlined before for the default installation.

Lastly, to save additional firmware space and RAM, follow the OpenWrt recommendation and at the end of the package list, add the following to enable batman-adv and include support for mesh encryption (e.g., use sae to authenticate mesh nodes):

| action | package |

|---|---|

| remove mesh encryption conflict | -wpad-basic-mbedtls |

| add mesh encryption | wpad-mesh-mbedtls |

| add the full batctl | batctl-full |

| add batman-adv | kmod-batman-adv |

Initial configuration

As mentioned before, we will not use the web UI in this tutorial, even if the OpenWrt image you’re using has LuCI installed by default. Instead, we will access our device and configure it using only SSH. So, open a terminal and ssh into your OpenWrt device, as follows

in which 192.168.1.1 is your OpenWrt device’s IP address (that’s usually the case after a fresh install but if it’s different, use the proper IP then). Because this is the first time using the system, you’ll need to set a password for the root user. You can do that by typing

passwd

and following the instructions. At this point, it’s good practice to label this device (e.g., node01) and take note of its MAC address. To find out the latter, type

ip link

and keep a record of the device’s name and its MAC address–if there are multiple different addresses, take note of all of them and their interface.

(Optional. Configure key-based authentication and disable password login. Reboot and check that ssh access methods are correctly configured.)

From this point forward, we will start editing files using vi. If you’ve not read the section about how to use vi yet, this is a good time to do so.

Default config for the hardware

Regardless of the hardware, before doing anything related to the mesh network, always take your time and study the default configuration found in /etc/config/. For reference, I usually go over the following:

- How many Ethernet ports?

- Are they labeled either LAN or WAN or there’s both?

- In

/etc/config/network, how is the router handling multiple Ethernet ports? If there’s both LAN and WAN, how is the router separating LAN from WAN? - If there is both LAN and WAN, how is the firewall handling them in

/etc/config/firewall? (Probably two zones, LAN and WAN, with LAN->WAN accept all but WAN->LAN deny all?) - In

/etc/config/dhcp, how is the device handling IP addresses? (Is there a DHCP server for LAN?)

And finally, look at the wireless settings (/etc/config/wireless):

- How many radio devices and their names? (e.g.,

radio0) - Configuration-wise, what is the device using by default vs. what is it capable of? (

iw list) - Is the radio enabled or disabled? (Keep/add

option disabled 1to disable it before configuration; to re-enable, simply comment this line out or set the value to0.) - Are there pre-configured wireless access points being broadcast? If yes, which

option networkis it using by default? (Likelylanor whatever the LAN interface is being called in/etc/config/network.)

For example, many wireless routers have LAN and WAN ports which are handled by a switch configuration with VLANs enabled to separate LAN from WAN. Take note of it; understand what is going on in the config files; play with them; then, continue. Also, take this opportunity to go over the Device Page to check if there’s any warnings or special configuration notes.

This understanding is instrumental to the way the device will be configured to play different roles in the mesh network and a good grasp of the device’s default settings will greatly reward you later on.

Updating and installing packages

(Only experienced users: If you used a default image, this is a good opportunity to remove unnecessary packages. See the OpenWrt FAQ for a reference of safe to remove packages, for example. If this is your first time playing with mesh, leave any unmentioned pkg alone until you get everything working as intended.)

In order to update and install packages, you need to give your device temporary access to the Internet. More often than not, if you have an existing network with access to the Internet on-site, then just connect the device to a router/switch via cable. If that doesn’t work, go ahead and configure your device to act like a dumb access point first. You can check that the device has access to the Internet by pinging google.com or 8.8.8.8, as follows

ping google.com

If it all looks good, it’s time to update the package list, as follows

opkg update

Optional. Upgrade all installed packages. Type opkg list-upgradable to find which packages can be upgraded and then opkg upgrade PKG, in which PKG is the package name. If opkg list-upgradable run into memory issues, try commenting out a few lines in /etc/opkg/distfeeds.conf and try again. Alternatively, it’s possible to use the following command to automatically upgrade all packages at once, per the opkg openwrt wiki examples:

opkg list-upgradable | cut -f 1 -d ' ' | xargs opkg upgrade

Be careful with mass upgrades though, especially if you’re running a device with limited memory. You might end up even bricking your device.

Now, let’s install the mesh-related packages and remove conflicting packages. First, remove wpad-basic-mbedtls with

opkg remove wpad-basic-mbedtls

then install batctl-full, batman-adv, and wpad-mesh-mbedtls with

opkg install batctl-full kmod-batman-adv wpad-mesh-mbedtls

It is up to you whether to install wpad-mesh-mbedtls or wpad-mesh-wolfssl or wpad-mesh-openssl. For a detailed description of the main differences, take a look at the TLS libraries that work on OpenWrt.

Make sure there are no error messages and if there are, troubleshoot them before proceeding.

Remove the connection that gave your device temporary access to the Internet. Then, reboot (type reboot in the terminal) and restart the SSH session with your laptop/PC still connected to the device via cable.

Depending on your hardware, you might run into issues while trying to make one or multiple radios operate in mesh point mode, owing to loaded modules and their default parameter values. Keep a close look at your device’s syslog file (run logread to output it to the terminal) for kernel related errors. In addition, take a look at the section Hardware-specific configurations for any comments related to the module used by your OpenWrt device.

Mesh node basic config

It is time to configure the basics of our mesh network and nodes. To do so, we will edit multiple files in /etc/config/ but first, let’s find out the capabilities of the detected radios in our wireless device, as follows

iw list

which will output something like this

Wiphy phy1

wiphy index: 1

max # scan SSIDs: 4

max scan IEs length: 2261 bytes

max # sched scan SSIDs: 0

max # match sets: 0

Retry short limit: 7

Retry long limit: 4

Coverage class: 0 (up to 0m)

Device supports AP-side u-APSD.

Device supports T-DLS.

Available Antennas: TX 0x7 RX 0x7

Configured Antennas: TX 0x7 RX 0x7

Supported interface modes:

* IBSS

* managed

* AP

* AP/VLAN

* monitor

* mesh point

* P2P-client

* P2P-GO

* outside context of a BSS

Band 2:

Capabilities: 0x11ef

RX LDPC

HT20/HT40

SM Power Save disabled

RX HT20 SGI

RX HT40 SGI

TX STBC

RX STBC 1-stream

Max AMSDU length: 3839 bytes

DSSS/CCK HT40

Maximum RX AMPDU length 65535 bytes (exponent: 0x003)

Minimum RX AMPDU time spacing: 8 usec (0x06)

HT TX/RX MCS rate indexes supported: 0-23

Frequencies:

* 5180 MHz [36] (17.0 dBm)

* 5200 MHz [40] (17.0 dBm)

* 5220 MHz [44] (17.0 dBm)

* 5240 MHz [48] (17.0 dBm)

* 5260 MHz [52] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5280 MHz [56] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5300 MHz [60] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5320 MHz [64] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5500 MHz [100] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5520 MHz [104] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5540 MHz [108] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5560 MHz [112] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5580 MHz [116] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5600 MHz [120] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5620 MHz [124] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5640 MHz [128] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5660 MHz [132] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5680 MHz [136] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5700 MHz [140] (21.0 dBm) (radar detection)

* 5745 MHz [149] (21.0 dBm)

* 5765 MHz [153] (21.0 dBm)

* 5785 MHz [157] (21.0 dBm)

* 5805 MHz [161] (21.0 dBm)

* 5825 MHz [165] (21.0 dBm)

valid interface combinations:

* #{ managed } <= 2048, #{ AP, mesh point } <= 8, #{ P2P-client, P2P-GO } <= 1, #{ IBSS } <= 1,

total <= 2048, #channels <= 1, STA/AP BI must match, radar detect widths: { 20 MHz (no HT), 20 MHz, 40 MHz }

HT Capability overrides:

* MCS: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff

* maximum A-MSDU length

* supported channel width

* short GI for 40 MHz

* max A-MPDU length exponent

* min MPDU start spacing

max # scan plans: 1

max scan plan interval: -1

max scan plan iterations: 0

Supported extended features:

* [ RRM ]: RRM

* [ CQM_RSSI_LIST ]: multiple CQM_RSSI_THOLD records

* [ CONTROL_PORT_OVER_NL80211 ]: control port over nl80211

* [ TXQS ]: FQ-CoDel-enabled intermediate TXQs

* [ AIRTIME_FAIRNESS ]: airtime fairness scheduling

* [ SCAN_RANDOM_SN ]: use random sequence numbers in scans

* [ SCAN_MIN_PREQ_CONTENT ]: use probe request with only rate IEs in scans

* [ CAN_REPLACE_PTK0 ]: can safely replace PTK 0 when rekeying

* [ CONTROL_PORT_NO_PREAUTH ]: disable pre-auth over nl80211 control port support

* [ DEL_IBSS_STA ]: deletion of IBSS station support

* [ MULTICAST_REGISTRATIONS ]: mgmt frame registration for multicast

* [ SCAN_FREQ_KHZ ]: scan on kHz frequency support

* [ CONTROL_PORT_OVER_NL80211_TX_STATUS ]: tx status for nl80211 control port support

Wiphy phy0

wiphy index: 0

max # scan SSIDs: 4

max scan IEs length: 2257 bytes

max # sched scan SSIDs: 0

max # match sets: 0

Retry short limit: 7

Retry long limit: 4

Coverage class: 0 (up to 0m)

Device supports AP-side u-APSD.

Device supports T-DLS.

Available Antennas: TX 0x3 RX 0x3

Configured Antennas: TX 0x3 RX 0x3

Supported interface modes:

* IBSS

* managed

* AP

* AP/VLAN

* monitor

* mesh point

* P2P-client

* P2P-GO

* outside context of a BSS

Band 1:

Capabilities: 0x11ef

RX LDPC

HT20/HT40

SM Power Save disabled

RX HT20 SGI

RX HT40 SGI

TX STBC

RX STBC 1-stream

Max AMSDU length: 3839 bytes

DSSS/CCK HT40

Maximum RX AMPDU length 65535 bytes (exponent: 0x003)

Minimum RX AMPDU time spacing: 8 usec (0x06)

HT TX/RX MCS rate indexes supported: 0-15

Frequencies:

* 2412 MHz [1] (20.0 dBm)

* 2417 MHz [2] (20.0 dBm)

* 2422 MHz [3] (20.0 dBm)

* 2427 MHz [4] (20.0 dBm)

* 2432 MHz [5] (20.0 dBm)

* 2437 MHz [6] (20.0 dBm)

* 2442 MHz [7] (20.0 dBm)

* 2447 MHz [8] (20.0 dBm)

* 2452 MHz [9] (20.0 dBm)

* 2457 MHz [10] (20.0 dBm)

* 2462 MHz [11] (20.0 dBm)

* 2467 MHz [12] (20.0 dBm)

* 2472 MHz [13] (20.0 dBm)

* 2484 MHz [14] (disabled)

valid interface combinations:

* #{ managed } <= 2048, #{ AP, mesh point } <= 8, #{ P2P-client, P2P-GO } <= 1, #{ IBSS } <= 1,

total <= 2048, #channels <= 1, STA/AP BI must match, radar detect widths: { 20 MHz (no HT), 20 MHz, 40 MHz }

HT Capability overrides:

* MCS: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff

* maximum A-MSDU length

* supported channel width

* short GI for 40 MHz

* max A-MPDU length exponent

* min MPDU start spacing

max # scan plans: 1

max scan plan interval: -1

max scan plan iterations: 0

Supported extended features:

* [ RRM ]: RRM

* [ CQM_RSSI_LIST ]: multiple CQM_RSSI_THOLD records

* [ CONTROL_PORT_OVER_NL80211 ]: control port over nl80211

* [ TXQS ]: FQ-CoDel-enabled intermediate TXQs

* [ AIRTIME_FAIRNESS ]: airtime fairness scheduling

* [ SCAN_RANDOM_SN ]: use random sequence numbers in scans

* [ SCAN_MIN_PREQ_CONTENT ]: use probe request with only rate IEs in scans

* [ CAN_REPLACE_PTK0 ]: can safely replace PTK 0 when rekeying

* [ CONTROL_PORT_NO_PREAUTH ]: disable pre-auth over nl80211 control port support

* [ DEL_IBSS_STA ]: deletion of IBSS station support

* [ MULTICAST_REGISTRATIONS ]: mgmt frame registration for multicast

* [ SCAN_FREQ_KHZ ]: scan on kHz frequency support

* [ CONTROL_PORT_OVER_NL80211_TX_STATUS ]: tx status for nl80211 control port support

Here, we are particularly interested in learning the following:

- How many radios there are (

phy0,phy1); - The supported modes of operation of each radio, and more specifically, that the device is indeed able to operate in

mesh pointmode, as shown underSupported interface modes:; - The total number of bands. In this example, each radio can use only one band but one uses

2.4GHzfrequencies (phy0,Band 1), while the other uses5GHzfrequencies (phy1,Band 2); - For each band, the acceptable channels, as shown under

Frequencies:.

With such information, we can now configure our radio devices in /etc/config/wireless, as follows

vi /etc/config/wireless

and then edit each config wifi-device stanza accordingly. In the TL-WDR4300, there’s two default config wifi-device stanzas–namely, one for the 2.4GHz radio (called radio0) and another for the 5GHz radio (radio1). After changing and adding a few additional options, mine usually look like the following:

config wifi-device 'radio0'

option type 'mac80211'

option channel '1'

#option txpower '20' ##uncomment and edit to override default transmission power in dBm

option hwmode '11g'

option path 'platform/ahb/18100000.wmac'

#option htmode 'HT20' ##uncomment and edit to override default high throughput mode

option country 'BR' ##must match your country code

option disabled '1' ##change to 0 to enable it

config wifi-device 'radio1'

option type 'mac80211'

option channel '153' ##all nodes must use the same channel

#option txpower '21' ##uncomment and edit to override default transmission power in dBm

option hwmode '11a'

option path 'pci0000:00/0000:00:00.0'

#option htmode 'HT20' ##uncomment and edit to override default high throughput mode

option country 'BR' ##must match your country code

option disabled '0' ##change to 1 to disable it

The comments in this and other config files are just for educational purpose. Feel free to remove them in your device’s config files.

In this guide, radio1 (5GHz) will be used for the mesh traffic under the channel 153, which means all other mesh nodes must use the same channel. However, radio0 (2.4GHz) will at times be used to create standard wireless access points (WAPs; 802.11b/g/n) for non-mesh clients, which means that none of the other nodes need to use the same channel with this radio. In fact, it is strongly advised that 2.4GHz WAPs in close proximity should use different channels–namely, channels 1 (2401–2423MHz frequency range), 6 (2426–2448MHz), or 11 (2451–2473MHz) because those are non-overlapping channels and therefore, do not interfere with each other. Because only mesh bridges will make use of radio0, the configuration indicates that it should be disabled by default.

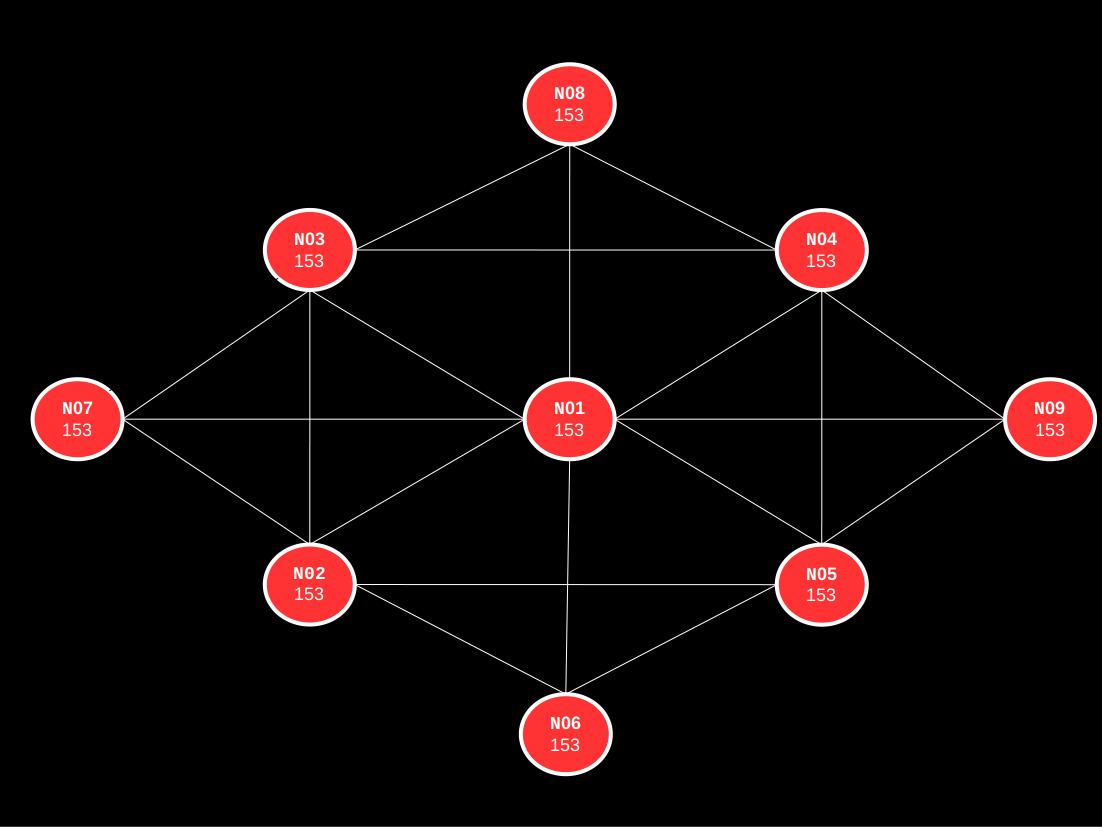

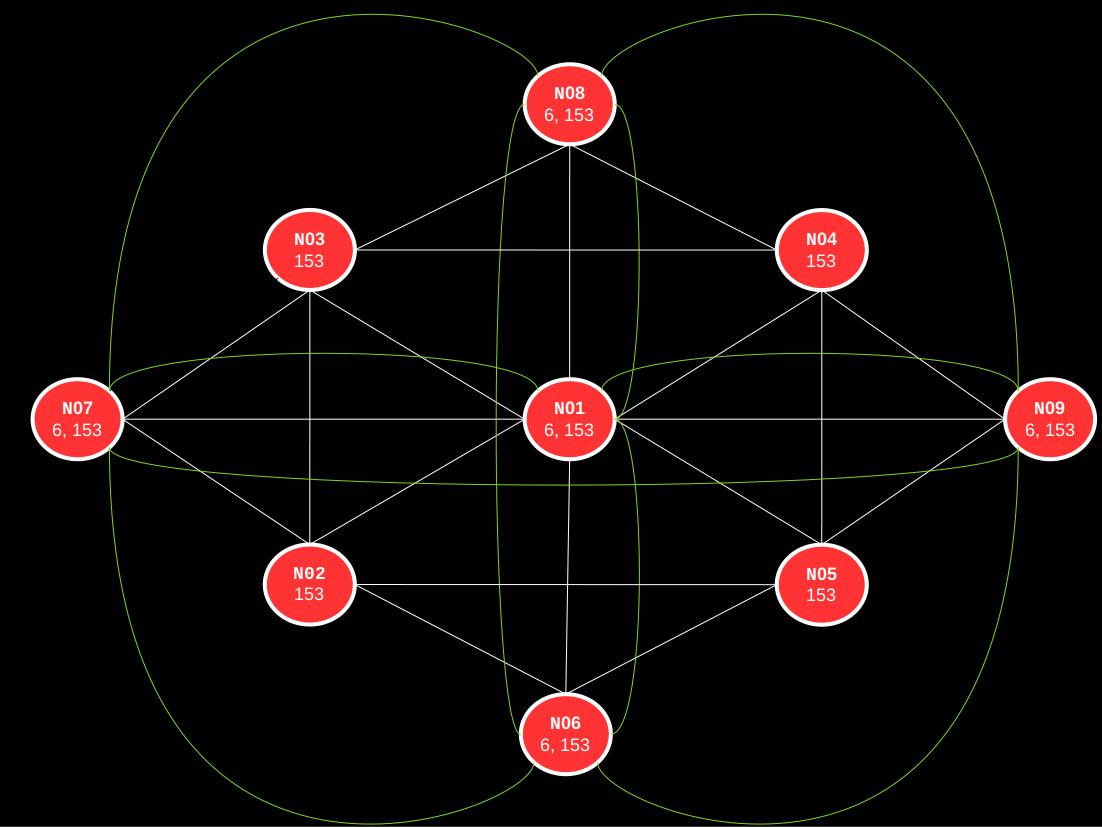

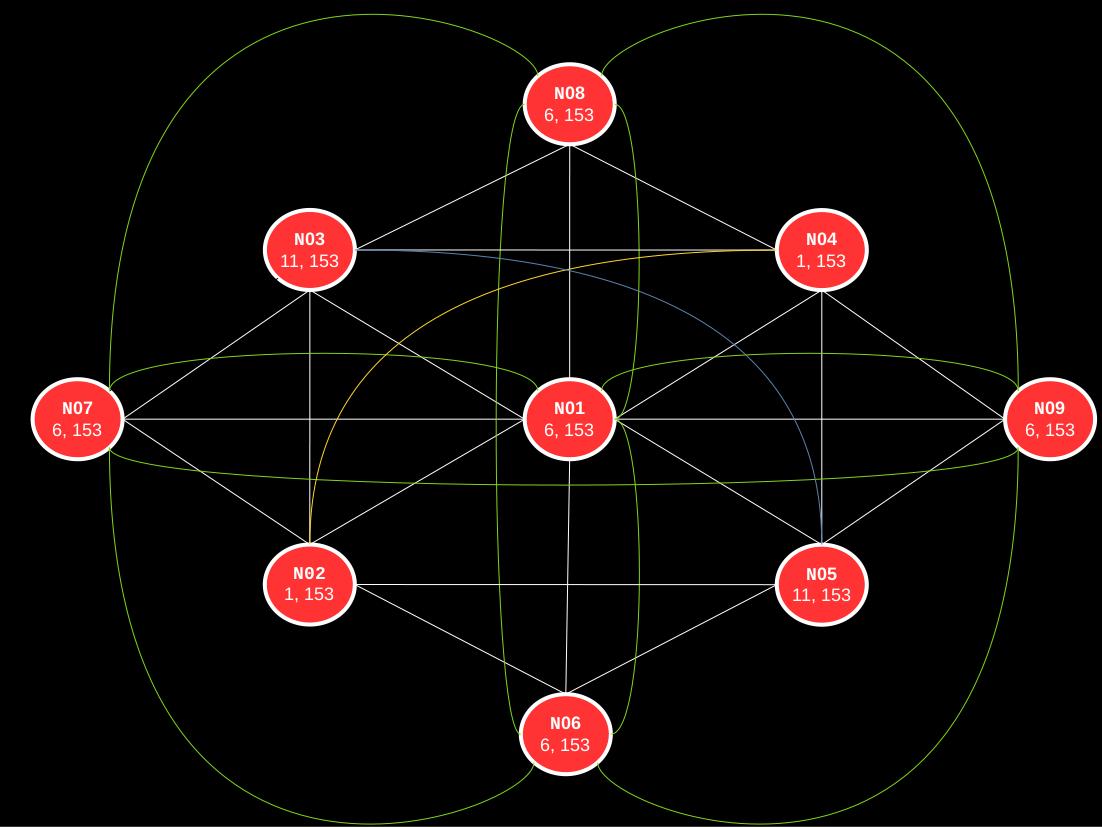

The segmentation between mesh and non-mesh wireless communication adopted in this guide is best summarized by the following illustration:

In addition, for HT20/HT40 devices, stick to HT20 if you are deploying the mesh in a crowded area, such as an apartment building; otherwise, the interference might make higher high-throughput (HT) actually less performant. Finally, remember to edit the country code before enabling the radio and follow country regulations when overriding the default transmission power (option txpower). More often than not, you should actually decrease the txpower rather than increase it. (For related material, see OpenWrt’s articles on Exceeding transmit power limits and Other transmit power issues.)

Comment out or delete any config wifi-iface automatically generated after a fresh install by adding a # at the beginning of each line or typing dd, as follows

#config wifi-iface 'default_radio0'

# option device 'radio0'

# option network 'lan'

# option mode 'ap'

# option ssid 'OpenWrt'

# option encryption 'none'

Then, at the end of the file, let’s add a wifi-iface for the wireless mesh, called wmesh, as follows

config wifi-iface 'wmesh'

option device 'radio1' ##must match the name of a wifi-device

option network 'mesh' ##mesh stanza in /etc/config/network

option mode 'mesh' ##use 802.11s mode

option mesh_id 'MeshCloud' ##mesh "ssid"

option encryption 'sae' ##https://openwrt.org/docs/guide-user/network/wifi/basic#encryption_modes

option key 'MeshPassword123' ##password in plain text

option mesh_fwding '0' ##let batman-adv handle routing

option mesh_ttl '1' ##time to live in the mesh

option mcast_rate '24000' ##routes with a lower throughput rate won't be visible

option disabled '0' ##change to 1 to disable it

Because all mesh nodes must operate on the same channel, use the same authentication, etc., multiple config options are often dictated by the “lowest common denominator” across all mesh nodes–that is, the best possible configuration that will work with all nodes, not just the ones with the best hardware and software available. For example, not all devices will necessarily be able to use SAE because it’s very new and therefore, won’t be able to connect to mesh networks that use it. Instead, you might want to set encryption to something like psk2+aes, which should be good enough for most devices out there. So, keep that in mind when configuring your mesh nodes.

Save the file and exit it.

Now we need to configure /etc/config/network to allow wmesh to use batman-adv. To do so, edit the network file, as follows

vi /etc/config/network

and let’s add an interface called bat0 at the bottom of the file, as follows:

config interface 'bat0'

option proto 'batadv'

option routing_algo 'BATMAN_IV'

option aggregated_ogms '1'

option ap_isolation '0'

option bonding '0'

option bridge_loop_avoidance '1'

option distributed_arp_table '1'

option fragmentation '1'

option gw_mode 'off'

#option gw_sel_class '20'

#option gw_bandwidth '10000/2000'

option hop_penalty '30'

option isolation_mark '0x00000000/0x00000000'

option log_level '0'

option multicast_mode '1'

option multicast_fanout '16'

option network_coding '0'

option orig_interval '1000'

The bat0 stanza has options with default values to facilitate fine-tuning later on. The specifics about each option is derived from the official batctl manual. For more details, refer to the Protocol Documentation and more specifically, the Tweaking section.

In very nichey cases of highly mobile nodes, it is recommended to disable aggregated_ogms and lower orig_interval.

Then, at the bottom of the /etc/config/network file, let’s add an actual network interface to transport batman-adv packets, which in our case will be the network used by wmesh in the /etc/config/wireless config file, namely mesh, as follows:

config interface 'mesh'

option proto 'batadv_hardif'

option master 'bat0'

option mtu '1536'

The maximum transmission unit (MTU) size should be anything between 1500 (usual size for Ethernet connections) and 2304 (usual size for WLAN connections). However, because batman-adv adds its own header to packets traveling through the wireless mesh network, it is suggested to set a minimum of 1528 instead. For a more detailed discussion, see Fragmentation in the official batman-adv wiki.

Save the file and exit.

Next, let’s reboot the device (type reboot in the terminal) and once it comes back online, ssh into it once again because we want to check that our batman-adv interfaces are up. To do so, type

ip link | grep bat0

and if the config is right, you should now see bat0 and wlan1 in the output. Similarly, we can use batctl to show us all active mesh interfaces, as follows

batctl if

If it all looks good, exit the ssh session, disconnect your laptop/PC from the wireless device (but keep it running nearby), and go ahead and configure at least one other node. This can be done manually just like you’ve just configured the current node. However, if your other mesh nodes are identical to the one you have already configured–that is, it is the same brand, model, and it is running the same OpenWrt version–then you can simply copy the modified files and then paste them on the /etc/config/ directory of the new device. To copy all such files from the configured device to your laptop/PC current directory, you can use scp, as follows:

scp -r [email protected]:/etc/config ./

which should create a config dir on your laptop/PC that has all the config files from the already configured device. Then, once connected to another default OpenWrt device, it’s just a matter of doing the reverse operation, as follows:

scp -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no -o UserKnownHostsFile=/dev/null \

-r ./config/* [email protected]:/etc/config/

Because we are starting SSH sessions with different machines that have the same IP address (192.168.1.1), we can include -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no -o UserKnownHostsFile=/dev/null to disable checking the known_hosts file and redirect discovery of the new key to /dev/null instead of your user’s known_hosts. Alternatively, you can manually edit or delete your user’s known_hosts file, which is usually found at ~/.ssh/known_hosts.

Afterwards, ssh into one of the configured mesh nodes and type

batctl n

which will show a table with the interfaces (wlan1), MAC address of the neighboring mesh nodes, and when each of them was last seen. Copy the MAC address (e.g., f0:f0:00:00:00:01) from each neighboring mesh node and ping them through the mesh (using batctl p) to see if they are all replying, as follows (press Ctrl+C to stop)

batctl p f0:f0:00:00:00:01

which should output something like the following if everything is working fine

PING f0:f0:00:00:00:01 (f0:f0:00:00:00:01) 20(48) bytes of data

20 bytes from f0:f0:00:00:00:01 icmp_seq=1 ttl=50 time=3.01 ms

20 bytes from f0:f0:00:00:00:01 icmp_seq=2 ttl=50 time=1.71 ms

20 bytes from f0:f0:00:00:00:01 icmp_seq=3 ttl=50 time=1.10 ms

--- f0:f0:00:00:00:01 ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 received, 0% packet loss

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 1.103/1.942/3.008/0.794 ms

Pat yourself on the back because you have successfully configured multiple mesh nodes!

Go ahead and configure all your mesh nodes the same way as before and only then move on to bridges, gateways, and VLAN configs, as described next.

Troubleshooting mesh issues

These are a few tips in case you run into issues when configuring gateways and bridges.

To test node to node connectivity, connect to a mesh node and use

batctl p MAC

in which MAC is another node’s MAC address. If the node does not reply, there’s an issue with batman-adv or its configuration. Try rebooting both nodes before doing anything else.

A more powerful tool to see what is going on in the mesh network is the tcpdump utility for batman-adv. To use it, connect to a mesh node and type

batctl td batX

in which batX is a batman-adv interface (usually bat0 but if you have more than one, then bat1, etc.). This is quite useful when configuring VLANs because it will show the VLAN ID of each client as well. In addition, it is possible to specify the VLAN ID in the td argument to constraint the output to one particular VLAN (e.g., batctl td bat0.1). Depending on the scale of your mesh network, you might need to filter the output because things can get wild with tcpdump really fast.

For more details, see the batctl manual or type batctl -h for cli usage information. Keep in mind that while many options can be set via batctl, those changes are ephemeral–that is, they won’t survive a reboot. To make permanent changes, you need to add/edit the respective option in the /etc/config/network file and batX stanza.

It is worth mentioning that if you’ve been following my suggestion to name and take note of each device’s MAC address, you can now create a file called bat-hosts in /etc/ that contains pairs of MAC address and name, as follows:

f0:f0:00:00:00:00 node01

f0:f1:00:00:00:00 node02

f0:f2:00:00:00:00 node03

f0:f3:00:00:00:00 node04

This makes it much easier to identify the mesh nodes when issuing a command like batctl n and other debug tables. As far as I’m aware, however, you have to create and update such file in each node because such information will just be available to nodes that have a bat-hosts file.

Finally, as mentioned before, keep an eye on your device’s syslog for errors. Module related issues are often associated with logged kernel errors (see the section Hardware-specific configurations) and wpa_supplicant has multiple mesh-specific error codes to help you debug connectivity issues. The syslog can be inspected via logread, as follows:

logread

For usage information, type logread -h.

Configuring common mesh networks

Here, we will see how to turn one or two of our configured mesh nodes into either a mesh bridge or a mesh gateway. To avoid repetition, the configuration of bridges and gateways is described in more detail in the first example, and only a few small differences and observations are highlighted afterwards. In addition, only IPv4 addresses and configurations were used but nothing prohibits the use of IPv6 in a mesh network.

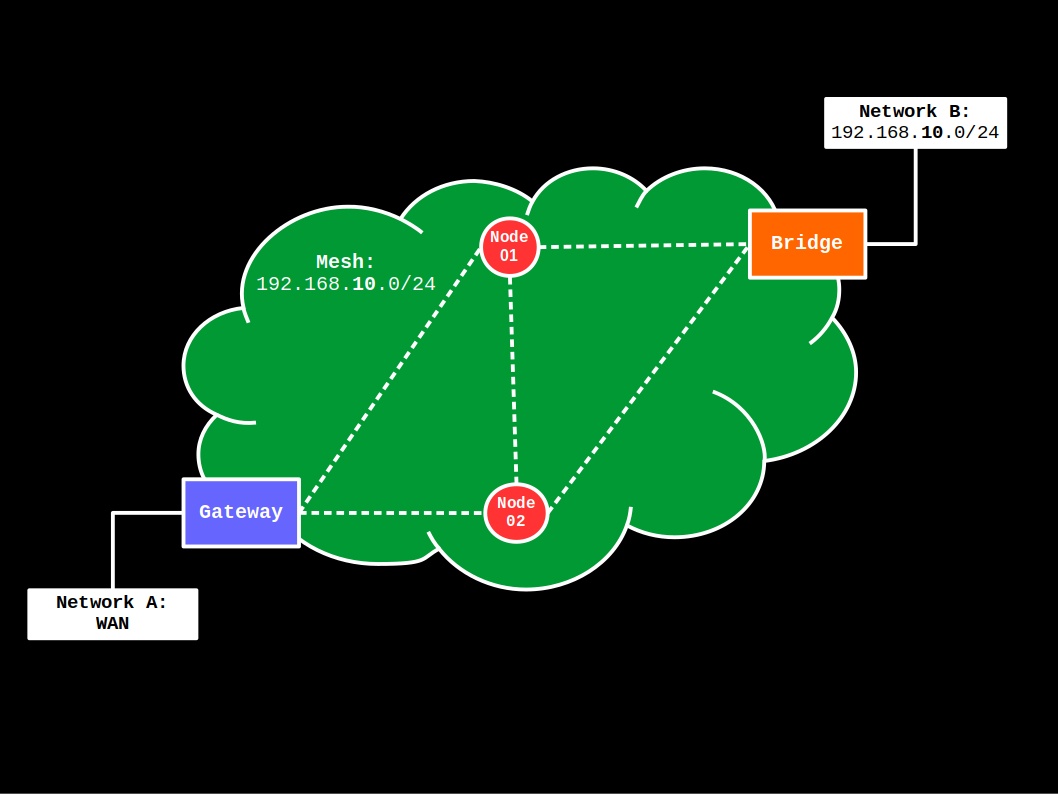

Gateway-Bridge

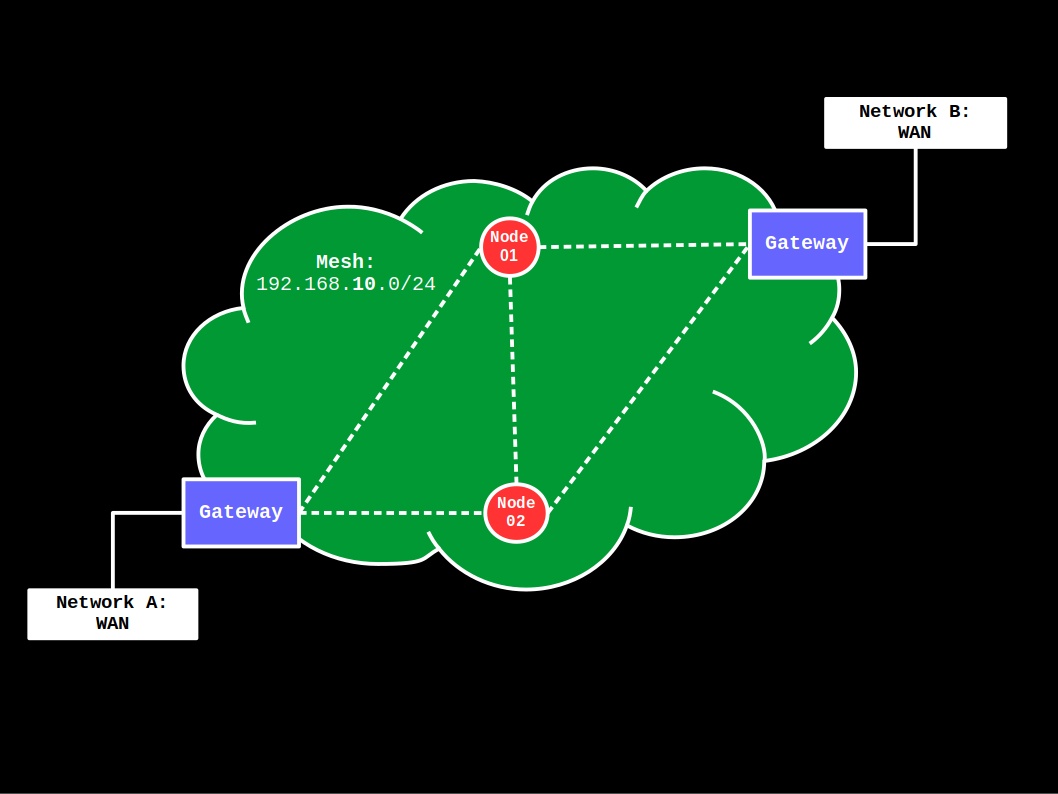

This first example applies to the following topology:

More specifically, the mesh has access to the WAN (Network A) via a gateway device and has a single, private network defined in the 192.168.10.0/24 IP range, which is used by both the mesh network devices and the Network B, non-mesh devices. The latter is enabled by a bridge device that works as an access point for non-mesh clients.

First, let’s configure our mesh gateway.

Mesh gateway configuration

Get one of the pre-configured mesh nodes that has at the very least two Ethernet ports, a LAN port and a WAN port. (This, of course, is not required for a gateway device because there are multiple ways to connect to WAN but having separate physical ports makes the explanation much simpler to follow. If that is not your case, just adapt the default configuration for your device accordingly.)

If you’ve configured this node as a dumb access point to temporarily give it access to the Internet while updating and installing packages, undo the configuration before proceeding because we will use both the firewall and dhcp config files in the gateway configuration.

Connect your laptop/PC to the mesh node via cable using the LAN port–this way, the mesh node’s IP address should still be 192.168.1.1. Then, ssh into the mesh node and let’s take a look at the /etc/config/network, as follows

vi /etc/config/network

At the beginning of the file, there should a bunch of config interface for loopback, lan, and wan, for example, as well as a default config device for the lan bridge, called br-lan, and. At the end, of course, there should be the mesh interfaces we previously created for the mesh node, namely bat0 and mesh. There are at least two options at this point:

- Create an entirely new local network for

bat0, calleddefault, at the expense of additionaldhcpandfirewallconfiguration; - Or use the original

lannetwork by simply bridgingbat0at theconfig devicebr-lanstanza, as follows:config device option name 'br-lan' option type 'bridge' list ports 'eth0.1' ##edit according to your device list ports 'bat0'

While the latter option is much easier than the former, we will choose the first here (i.e., create a new local network from the ground up) because it makes this tutorial compatible with multiple devices (switched or switchless) and it allows us to keep the original lan (192.168.1.0/24) as a management/debugging network. (Later on, we will see how to bridge the original lan with any bat0 VLAN, for example, so the original lan becomes accessible to the mesh as well. For now, keep it simple.)

At the bottom of the /etc/config/network file, let’s add the following two stanzas:

config device

option name 'br-default'

option type 'bridge'

list ports 'bat0'

config interface 'default'

option device 'br-default'

option proto 'static'

option ipaddr '192.168.10.1' ##static address on the new 192.168.10.0/24 network pool

option netmask '255.255.255.0'

list dns '1.1.1.1' ##comment out to enable cloudflare dns

list dns '8.8.8.8' ##comment out to disable google dns

The first stanza (config device) creates a bridge (layer 2) for the default network, while the second stanza (config interface 'default') creates the proper default network (layer 3) at the 192.168.10.0/24 pool, then sets a static IP address for this device at 192.168.10.1 and broadcasts to any client that they should use the external DNS servers 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8.

Save the file and exit it.

Next, let’s edit the /etc/config/dhcp config to run a DHCP server on the new interface, as follows

vi /etc/config/dhcp

and at the end of the file, add the following

config dhcp 'default'

option interface 'default'

option start '50' ##start leasing at addr 192.168.10.50

option limit '100' ##max leases, so for 100, leased addr goes from .50 to .149

option leasetime '6h'

option ra 'server'

Save the file and exit it.

Finally, let’s edit the /etc/config/firewall config. Many things that can be done at the firewall level and for this reason, it’s often the most overwhelming part of the configuration. Fortunately, in our case, all that we need to do here is simply copy the original lan config for the new default. That is, anything that has lan we will

- copy the related config;

- paste it immediately below the equivalent

lanconfig; - and then change

lanfordefaultin the new config.

Start by editing the firewall config file with vi, as follows

vi /etc/config/firewall

then the first set of configs we will add (immediately below the equivalent lan config) is the zone settings, namely

config zone

option name default

list network 'default'

option input ACCEPT

option output ACCEPT

option forward ACCEPT

the second set of configs will be for the forwarding settings, namely

config forwarding

option src default

option dest wan

and that is it!

Optional. At the end of the firewall config file, there’s a bunch of examples that you could use as template for more avdanced usage of this device’s firewall. Feel free to play around with them once you get everything up and running.

Save the file and exit it.

Optional. Because we’re not going to use IPv6, I suggest (a) disabling odhcpd altogether (run /etc/init.d/odhcpd stop && /etc/init.d/odhcpd disable) and (b) comment out any related IPv6 configuration in the files we just edited as well (e.g., remove configuration and references to wan6).

Reboot the device and connect the WAN cable to the device’s WAN Ethernet port.

Once the device comes back online, ssh into it. Then, let’s check the new configuration. First, type

ip a

and as before, there should be bat0 and wlan1 interfaces, but now, your gateway device should have the static IP 192.168.10.1 in the new 192.168.10.0/24 network under br-default.

Similarly, because we preserved the original lan configuration, the device will continue to have the static IP 192.168.1.1 in the 192.168.1.0/24 network under br-lan. This means it should always be reachable at its original IP address with an Ethernet cable directly connected to one of its LAN Ethernet ports.

If you don’t see the static IP on the new network, then review the files we have just configured because there’s likely a misconfiguration. Don’t expect to get things working until you fix this issue.

Mesh bridge configuration

The configuration of a mesh bridge is much simpler than of a mesh gateway because contrary to the gateway config, our mesh bridge doesn’t require the use of a DHCP server and firewall. In fact, both services will be disabled in a mesh bridge and instead, the ony thing we will do is join interfaces to make them look like a single one to any connected device.

As before, get one of the other pre-configured mesh nodes and to start things off, we will configure it as a dumb access point. Follow the instructions in the OpenWrt documentation, except for the following when configuring the original lan interface:

- Add

bat0to a newlist portsentry in the bridge stanza used by thelaninterface, namelybr-lan; - Set a static IP for the device on the

192.168.10.0/24network, such as192.168.10.10, pointing to our configured gateway at192.168.10.1; - After all is done, rename every

lanentry fordefaultto make it consistent with the gateway configuration. This, of course, is optional.

Once done, the configuration of the original lan interface and its br-lan bridge, which are now called default and br-default, respectively, should look something like this:

config device

option name 'br-default'

option type 'bridge'

list ports 'eth0.1'

list ports 'bat0'

config interface 'default'

option device 'br-default'

option proto 'static'

option ipaddr '192.168.10.10'

option netmask '255.255.255.0'

option gateway '192.168.10.1'

option dns '192.168.10.1'

After applying this configuration, it will let any non-mesh clients to join the mesh via Ethernet cable–that is, by connecting a cable to one of the LAN ports of the mesh bridge device. As long as the gateway is reachable, everything should work like a standard network, you could use the device’s own switch or connect the device to a switch and manage things there, and so on.

Save the file and exit it.

Similarly, you can create a wireless access point (WAP) for non-mesh clients, and the instructions in the dumb access point documentation will work just fine because it uses a network that is bridged with our mesh–namely, the original lan. To avoid confusion, make sure to use a different SSID for the WAP(s) than the mesh_id used for the mesh. In addition, use a different radio for the WAP(s) and set them to operate on different channels. If that is not possible, that is probably okay for most home users but keep in mind that node hoping will start affecting performance quite noticeably.

(Optional.) To illustrate, let’s create a simple 2.4GHz WAP for your home devices that will make use of the default network. This can be done by editing the /etc/config/wireless file as follows:

-

In the 2.4GHz radio stanza (

radio0), setoption disabledto'0'to enable it:config wifi-device 'radio0' option type 'mac80211' option channel '1' #option txpower '20' option hwmode '11g' option path 'platform/ahb/18100000.wmac' #option htmode 'HT20' option country 'BR' option disabled '0' -

At the bottom of the file, create a new

config wifi-interface 'whome'stanza that configures an access point (option mode 'ap') that will make use of thedefaultnetwork. It should look similar to the following one when done:config wifi-iface 'whome' option device 'radio0' option network 'default' option mode 'ap' option ssid 'HomeWAP' ##edit it option encryption 'psk2+aes' ##https://openwrt.org/docs/guide-user/network/wifi/basic#encryption_modes option key 'MyStrongPassword123' ##edit it option disabled '0' -

Save the file and exit.

Finally, in the terminal, make sure to disable dnsmasq, odhcpd, and the firewall, as follows

/etc/init.d/dnsmasq stop && /etc/init.d/dnsmasq disable

/etc/init.d/odhcpd stop && /etc/init.d/odhcpd disable

/etc/init.d/firewall stop && /etc/init.d/firewall disable

Reboot your device and on your laptop/PC, disable networking altogether to force it to get a new IP from the bridge when it comes back online–alternatively, just disconnect the Ethernet cable.

Once the bridge is back online–wait at least a minute or two to give it enough time to connect to the mesh first–re-enable networking on your laptop/PC (or reconnect the Ethernet cable) and it should receive an IP addr from our mesh gateway in the 192.168.10.0/24 network (on a Linux distro, type ip a or ip addr or ifconfig), the bridge node should now be reachable at 192.168.10.10, and you should be able to access the Internet from your laptop/PC through the mesh (try ping google.com, for example).

If something doesn’t work, review the config files mentioned here and then go over the ones for the gateway, reboot all mesh nodes (gateway first, then nodes, then bridge) and test again.

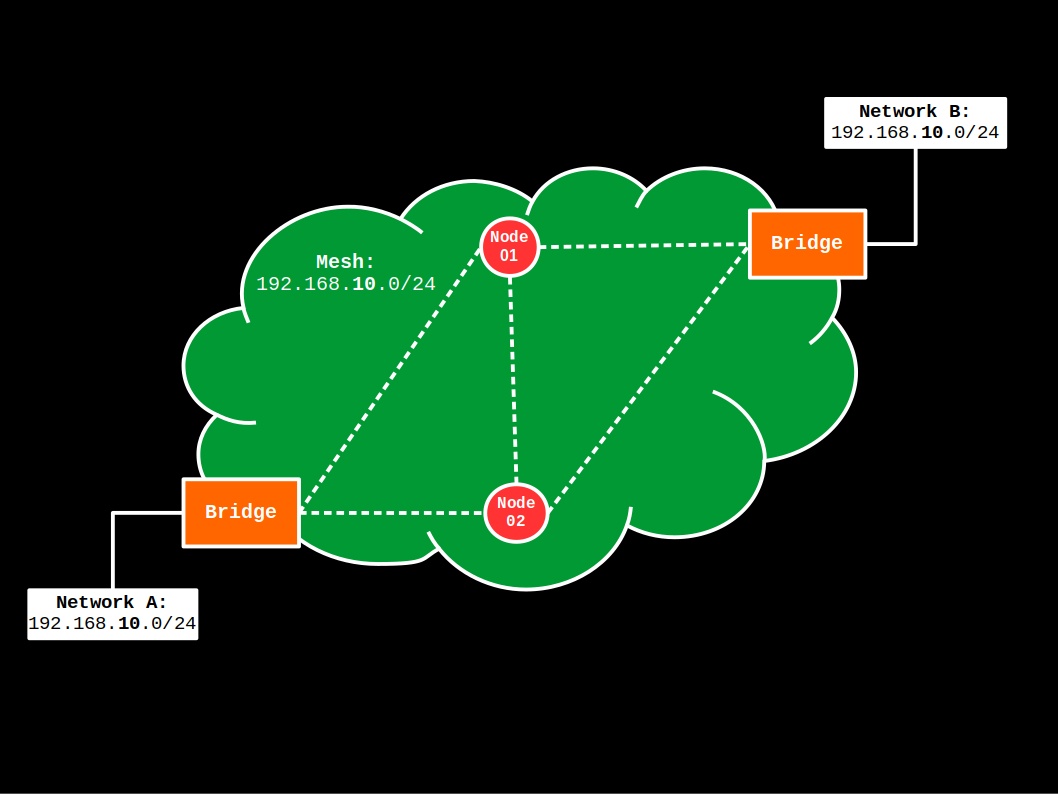

Bridge-Bridge

This second example applies to the following topology:

Contrary to the first example, there’s no mesh gateway device and as such, this topology could be used to extend an already existing private network (Networks A and B) over the wireless mesh (all defined in the 192.168.10.0/24 IP range). However, to make matters simple, we will assume that the existing network has a gateway/firewall in either Network A or B that can be found at the IP addr 192.168.10.1, and there’s a DHCP server being advertised on the network. (If your existing Networks A and B are not defined in the 192.168.10.0/24 IP range, just edit your previous config files accordingly and the mesh network will follow your existing network instead.)

Config-wise, the mesh bridges in this topology are configured exactly as in the first example, except for the following differences in the configuration of the /etc/config/network config file:

-

Each mesh bridge should have a different static IP address in the

defaultinterface, as indicated byoption ipaddr. For example, the first mesh bridge will haveoption ipaddr '192.168.10.10', while the second mesh bridge will haveoption ipaddr '192.168.10.11'; -

The